Terra Incognita was a Latin term used on maps from the Age of Discovery to denote unexplored territories. It’s a perspectival term. Because, of course, there were people like the Tupinambá actually living in those seemingly unexplored lands on Martin Waldseemüller’s map. The places the Tupinambá knew intimately — where they fished or hunted or celebrated or slept — were not Terra Incognita to them. But to the Europeans embarking on their voyages each new cove and settlement was a curve or mark to be made on a map. It was a matter of perspective. A matter of technology. Some small matter of hubris.

It remains a question of all of these things in the Information Age. The optimism and hubris of Big Data appear to be unrivaled – What don’t we know in the age of Big Data? By tapping mystic rhythms with our fingers and staring into squares of light we traverse great oceans of distance. As we zoom around global networks on a variety of devices, there is the common perception that we could go anywhere, learn about anything, connect with anyone.

Except we don’t.

Ethan Zuckerman calls this “Imaginary Cosmopolitanism”. We imagine ourselves to be citizens of the world because of our unprecedented, privileged access to information. But there are a couple of things working against our cosmopolitanism. The foremost is our very human impulse towards “homophily”. Social scientists like Zuckerman, Fiore and Donath, and McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook show us how homophily—the tendency for us to group ourselves with those most like us—is as alive and well on the World Wide Web as it is in physical space.

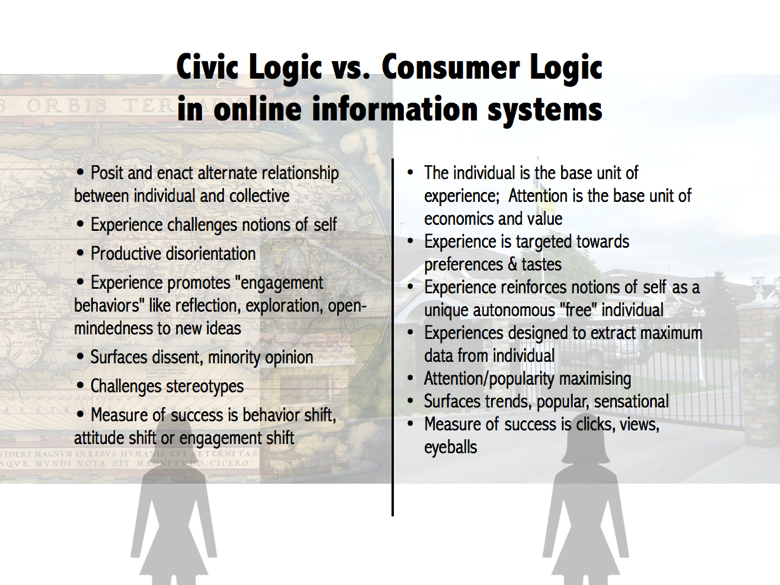

The other half of the Imaginary Cosmopolitanism equation is technological. The technologies that most enable our informational selves (powerful search algorithms like Google, social sharing sites like Facebook and recommendation systems like Amazon) are the ones that reinforce our homophily by giving us what we want, what our friends want, and what people like us want. From a design perspective these information systems follow consumer logic which is based on criteria of similarity and promotion of the popular.

This works great most of the time. I want something. I tell Google. Google gives me the thing.

What this does not work well for is the discovery of difference, the surfacing of minority opinion, and the engagement of perspectives other than our own. We might imagine ourselves to be citizens of the world but in fact live in informational gated communities talking only to our little pockets of humanity.

Civic Logic: Information Design for Encountering Difference

How can we engineer information discovery systems for openness, risk-taking and exploration? What would it mean to emphasize civic logic rather than consumer logic as a design criteria for information systems?

Part of the design challenge is making people feel safe enough and interested enough to explore information that they do not perceive as having immediate utility to them. I think about this in a performative way – how can our information technologies stage encounters with people, knowledge or information outside our comfort zones, biases and habits?

The other part of the design challenge is making people aware of how small, ephemeral actions, such as reading a webpage, liking a Facebook post or watching a movie, have a part to play in a vibrant, diverse and democratic networked public sphere.

There is increasing scholarship, journalism, and experimentation in this problem space and there should be more.

Terra Incognita: An Experiment in Cosmopolitanism

What might civic logic look like in action? Together with Ethan Zuckerman and Matt Stempeck at the MIT Center for Civic Media, I have been building an information discovery system with civic logic in mind. In our case, we are particularly interested in the dimension of geography. What cities and countries in the world do we read about? Which do we systematically ignore? When we do read about faraway places – like Syria – mainstream news coverage tends to be oriented towards conflict and violence. How can we surface interesting, stereotype-busting information about remote geographies? How can we connect people to parts of the world where they never previously had interest?

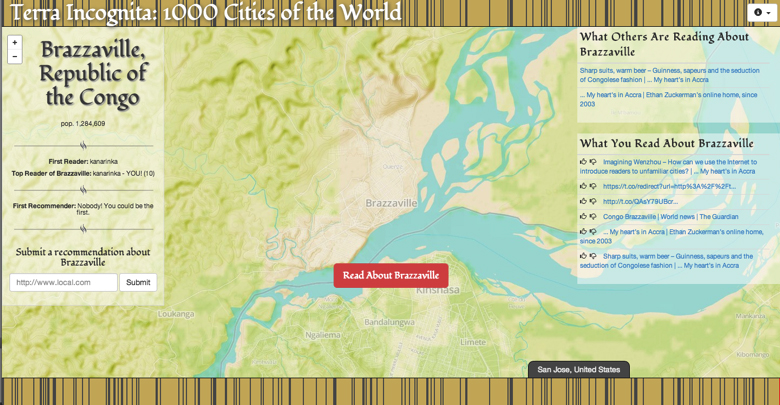

Terra Incognita: 1000 Cities of the World is a global news recommendation system and game. It has three goals: 1) To provoke reflection on the geographic dimensions of your Internet browsing in relation to others’. 2) To seduce you into an explorational mindset and privilege exploration over “what you want”. 3) To encourage the discovery of geographically diverse information on the Internet.

The main user experience of Terra Incognita is an intervention into your Internet browsing experience. Technically, it is an extension for the Chrome browser, a liminal space for software operation where you have options which are not typically available to regular websites. Each time you open a new Tab, Terra Incognita shows you a city that you have not yet read about and gives you options for reading about it. Chelyabinsk (Russia), Hiroshima (Japan), Hagåtña (Guam) and Dhaka (Bangladesh) are a few of the places where you might end up.

From a city like Dhaka, there are several options to pique the user’s interest and intrigue them enough to distract them from their previous task at hand. If other users in the system have read about that city, a scrolling list of those stories shows in the top right corner of the screen. For the bold and adventurous, there is a large red button “Read about Dhaka” in the center of the screen. This functions akin to Google’s “I’m feeling lucky” button to take them to a single news story recommendation about Dhaka.

Four “Read about Dhaka” recommendations for Dhaka, Bangladesh: An announcement about Bengali holidays in Google calendar, a BBC article about the owners of the Bangladesh fire factory, a Global Voices story about the arrest of teenage bloggers in Dhaka, and a photo slideshow from the Huffington Post about the Red Glass festival celebration in Dhaka on April 13th.

Figuring out how to collect high-quality, stereotype-busting recommendations about the top 1000 cities in the world was no small problem. Our upcoming user study will inform us as to how well we have solved this problem. Using our ideas around civic logic as our guide we chose to follow a criteria of multiplicity, transparency, potential for reflection and prioritisation of alternative voices.

The recommendations are delivered through many multiple sources: 1) stories that other users read or recommended in the Terra Incognita system 2) stories about that city that are being shared across the Internet but giving priority to participatory media sites like Global Voices 3) stories that we crowdsourced through an open call 4) stories that people had originally saved through the Instapaper service and 5) stories curated in partnership with with editors from Global Voices. Even with these multiple sources of recommendations there were many blank spots in our recommendation system that we had to address. For example, China accounts for about 20% or 200 cities in Terra Incognita, but there was very little information in English about many medium-sized Chinese cities available through our recommendation channels. In this case, we worked with a media scholar from China to manually compile a list of English-language news sources by city.

While designing Terra Incognita: 1000 Cities of the World with civic logic in mind, numerous other questions came to mind. We hope to answer some of these through the user study but we need more brains working on these questions. How do you make algorithms, whose work happens behind the scenes, transparent and public? What kind of online reading leads to increased reflection? How do you balance civic goals with maintaining user interest and engagement? How can information systems engender productive disorientation – an encounter with difference that unseats the user, however briefly, and invites them to recalibrate their worldview?

About the author.

Catherine D’Ignazio is an artist, software developer and educator. Her artwork is participatory and distributed – a single project might take place online, in the street and in a gallery, and involve multiple audiences participating in different ways for different reasons.

D’Ignazio’s expertise creating both impermanent and permanent projects will add a valuable voice to the discussion. Through her project, Terra Incognita, she focuses on the design challenge of how to engineer information discovery systems for risk-taking and exploration that differ from homogeneous, grouped communities formed on the internet.