Change is constant. It insinuates impermanence and can be exciting or devastating. Living in the fast growing city of Raleigh, I’ve seen a tremendous amount of change since moving here in 2002 – some exciting and some devastating.

I practiced architecture for seven years before serving on the Raleigh Planning Commission. I worked on buildings that took at least a year to design and often as much time to build. The design process for each project stole part of my heart and soul, as well as most of my weekends. I did not mind, because I knew I was making places for people – marks on the earth that would last my lifetime and beyond. This is one of the great joys and responsibilities of being an architect.

Before my experience with the Planning Commission, I was not familiar with the analysis, discussion, and debate that leads to change in our city, almost none of which directly addresses the value of design. Most astounding to me was the manner in which a new development slated to replace an existing architectural gem was presented to the city in 2011. The attorney representing the case rightfully pointed out that Raleigh was ready for greater density at 401 Oberlin Road. To further his point, he also stated that the 1957 government building designed by Leif Valand, was “obsolete”. While I concurred with the statement about density, I was horrified that any building just over fifty years old could be considered obsolete, let alone a beautiful, contextually sensitive work of art that so strongly held the corner of an important intersection for both cars and pedestrians.

Watching the demolition of 401 Oberlin Road was heartbreaking, because I knew what the replacement was to look like, which was sadly a building that simply works.

Important buildings on important sites all over Raleigh are being designed and built based on several factors; market value of the land, cost of construction, number of units needed to repay bank loans, and keeping neighbors happy. Landscape design associated with these buildings is rarely more than required by code, which is quite minimal. Proportions seem prescriptive and the material palettes are completely predictable.

But the buildings “work”. They are approved and they are built.

As designers in a growing city, it is impossible to reject change, as well as the continuously changing life span of our buildings. But, it is possible to approach each building’s design with the same vigor and passion as Leif Valand when he designed 401 Oberlin Road as a building to last far more than 50 years. No matter how permanent or impermanent, buildings should be designed so they are meaningful while they are here and missed when they are gone.

How can designers embrace change and create buildings that are more than simply functional?

In 2010, my business partner, Matt Griffith, and I set out to open an architecture practice in Raleigh called in situ studio. The name of our firm announces the importance of place. In Latin, in situ means, “in its natural position”. For us, this means paying attention to several factors of context – the site and surroundings, the time in which we are building, and the people who will be affected by our work.

In our practice, we have found that doing more that just what works takes a willingness to embrace constraint, persistence and education, and celebration.

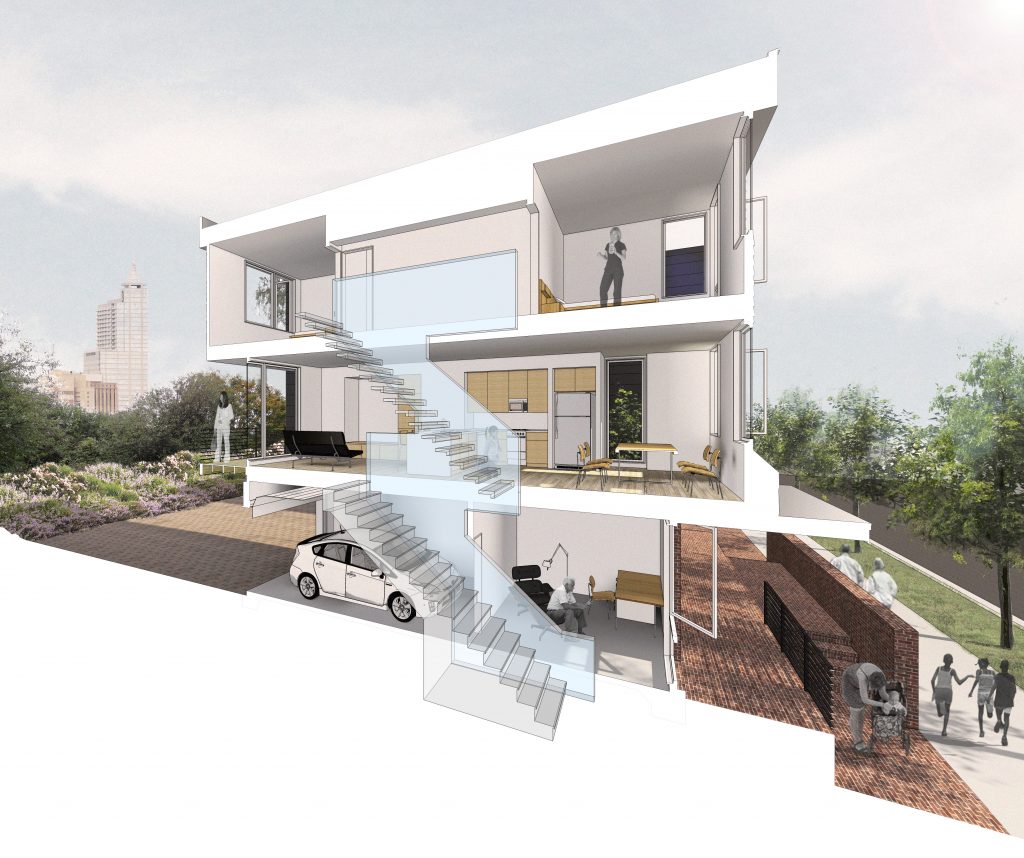

Our design of ten townhomes at 520 S Person Street in downtown Raleigh for the Downtown Housing Improvement Corporation (DHIC), is an example of a project that attempted to capture all of the above. The site is located in the recently designated Prince Hall Historic Overlay District, immediately southeast of the center of downtown. Three single family homes used to occupy what is now one parcel. There is rich a history of community and place in the neighborhood, a factor that we immediately observed and documented. We met with the neighborhood on multiple occasions to gain their input, analyzed each contributing structure in the district, and had preliminary design reviews with the Raleigh Historic Development Commission, the Appearance Commission, and the Urban Design Center. This collection of information informed us of the numerous constraints within which we were to design.

The design for 520 S Person Street does not mimic any surrounding structure. It does not look like the many other multi-family development constructed in Raleigh over the last ten years. It will be constructed of materials and methods that reflect the 21st century. It is as unique to its site and surroundings as every building should be, all the while inspired by dozens of architectural elements and desires expressed by the neighbors. Unfortunately, the design still received criticism because it was unfamiliar, but our design team remained persistent. We spent hours educating those most critical about the design that it will not feel out of place. Our team did this by showing specific ways in which our design response hearkened back to existing structures within the area and was contextually sensitive.

After more than a year of meetings with constituents, stakeholders, neighbors, and authorities having jurisdiction, we gained approval of the design. It will start construction summer, 2014. Celebration of the approval and soon to be habitable building is critical. We believe that if we show that unique design can be approved and built, there will be more of it in the area. Perhaps more designers will care less about what simply works and more about their role in giving our city its identity – no matter how permanent or impermanent the work may be.

About the author.

Erin Sterling Lewis is a Co-founder and Principal at in situ studio, an architecture firm in Downtown Raleigh. She is a native of Illinois and grew up in Mississippi. She earned a BArch from the University of Kentucky in 2002. Before founding in situ studio, Erin worked for nine years at Frank Harmon Architect PA, where she played an integral role in various projects, including the Merchants Millpond State Park Visitor Center, the Walnut Creek Wetland Center, Horseshoe Farm Park, the AIA NC Center for Architecture and Design, and the First Presbyterian Church Renovation.

Erin is involved in various community outreach and volunteer programs. From 2004 to 2006, Erin served on the Raleigh Historic Districts Commission. She has served on the Raleigh Planning Commission since 2009, and currently serves on the advisory board for the NCSU College of Design School of Architecture. Erin has been an invited juror for the City of Raleigh Sir Walter Raleigh Awards in 2007 and 2010, as well as the 2010 North Carolina Solar Center NC Sustainable Building Design Competition. In early 2010, she volunteered to teach a course on sustainable design at the NCSU Encore Center for Lifelong Enrichment. In 2010, Erin joined the AIA North Carolina (AIA NC) Board of Directors. On the Board, she serves as the Young Architects Forum (YAF) Director as well as Chair of the Programs Committee, which focuses on Program Development, Educational Outreach, and Design Exhibitions for AIA NC’s Center for Architecture and Design.

Erin lives with her family in a 1923 bungalow near downtown Raleigh.