Public Interest Design in Transition

by Lauren Krutchen

“The human backside is a dimension architects seem to have forgotten,” said William H. Whyte, a well-known American urbanist (“William H. Whyte”). Whyte is describing how, historically, architects failed to include human perspective in their designs. However, Whyte, and a handful of other designers, realize that the most important goal of a design is that it responds to the needs of the people and communities it’s made for. Public interest design is a human-centered practice that enables designers to serve specific needs in communities, with an emphasis on social, economical, and environmental developments (“Public Interest Design”). It relies on a participatory approach of community development in which designers assess the needs and resources existing within a community and involve citizens in the process of “putting creative abilities to practical use to improve communities,” according to Bryan Bell, architect and founder of Design Corps (“Bryan Bell, AIA”). Public interest design got its start in 1968 during the community design movement, in which community design centers were established all across the U.S. to provide design services, like affordable housing, to neighborhoods in need (“Public Interest Design”). In the 1990s the importance of public interest design began to grow, particularly in the social responsibility of architecture. Organizations like Architecture for Humanity, BaSiC Initiative, Project H, and Design Corps began to provide design services for larger communities and are building on a larger legacy of designing with people. Designing for these communities benefits societies in terms of their mental, social, environmental, and economical health. Currently, public interest design is changing design in the way that it focuses on a community of people still often ignored by designers, developing a methodology of thoughtful principles for how they engage with communities.

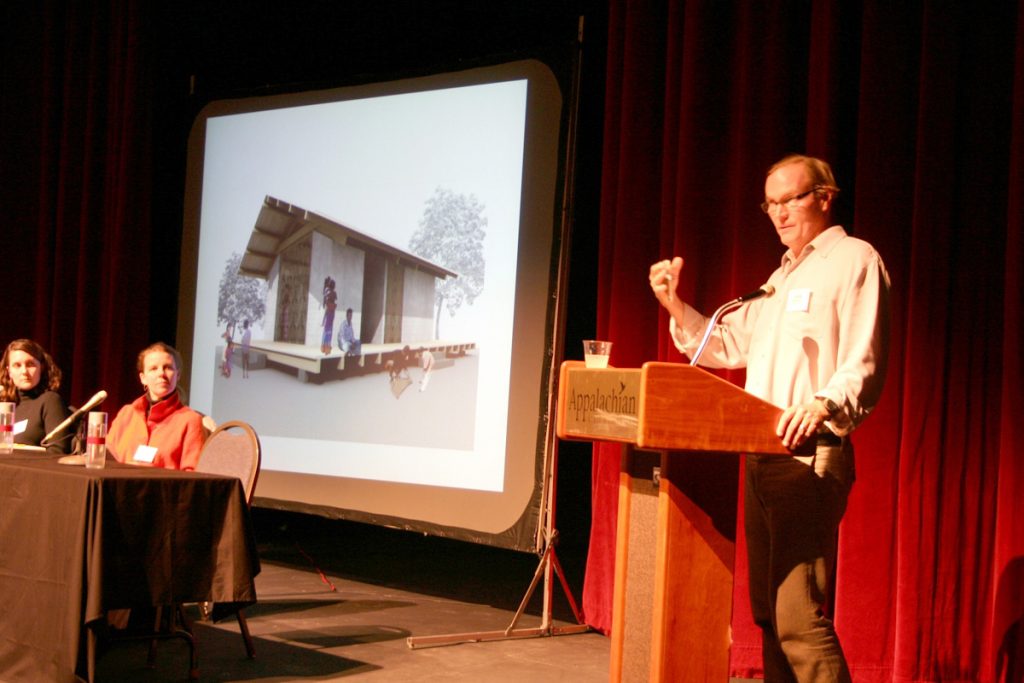

Architect Bryan Bell founded Design Corps with the goal to create positive change within underserved communities “by using design advocacy and education to help them shape their environment and address their social, economic, and environmental challenges,” as he stated in a lecture for the NCSU College of Design. Typically, when a community is unable to afford expensive architectural design, the community suffers and is left unnoticed. Design Corps realizes the struggle of these communities and faces the challenge of figuring out how to help them with public interest design. Bell has initiated many projects that accommodate the “98% without access to architects” by first involving the people who are in need in the decision making process (“Bryan Bell, Jr., AIA (1960-)”). Unlike most designers of the past and present, Bell fully immerses community members into the design process, asking community members what it is they want to see get done in their community. According to Bell and the Design Corps foundation, their mission is not realized until “people are involved in the decisions that shape their lives.”

One of Design Corps and Bell’s projects in 2003 was a series of migrant bathhouses built by NCSU College of Design students. Once Bell found out about the unsanitary conditions faced by migrant farm workers in Sampson County, NC he made it his mission to do something about it. After obtaining a $25,000 anonymous donation, Bell and his students were able to complete the bathhouse using other ways to save money on equipment. Leftover lockers were used from a project at Cary Elementary School, the roof was made from old plastic barrels from Edenton Cotton Mill, and the floors were made from aluminum street signs, which were a surplus from the NC Department of Transportation (“Bryan Bell, Jr., AIA (1960-)”). This project is just one example of how Bell went out of his way to ensure the needs of the community he was working with were met, keeping it in their budget and ideals. Not many designers would go through such great lengths to do this, but Bell shows that a transition into public interest design would have huge benefits on the public.

William H. Whyte, a mentor for the Project of Public Spaces, studied urban spaces in 1969, and advocated for a bottom-up approach to designing public spaces in which the design starts with an understanding of how the people ultimately use the space, and would like to use the space (“William H. Whyte”). He believed in order to do this one must just talk to the people, and learn about them and what they want and need to see in their communities in order to make them livable.

He said that designers need to “look hard, with a clean, clear mind, and then look again – and believe what you see,” therefore getting rid of all previous biases and focusing on what really matters to the community members (“William H. Whyte”). Whyte believed that it’s important to adhere to the people of the communities’ needs because it ultimately improves the quality of life within individual members and society as a whole. Although Whyte’s observational approach to designing for public spaces has been successful, there is more that can be done to ensure communities’ needs are fulfilled.

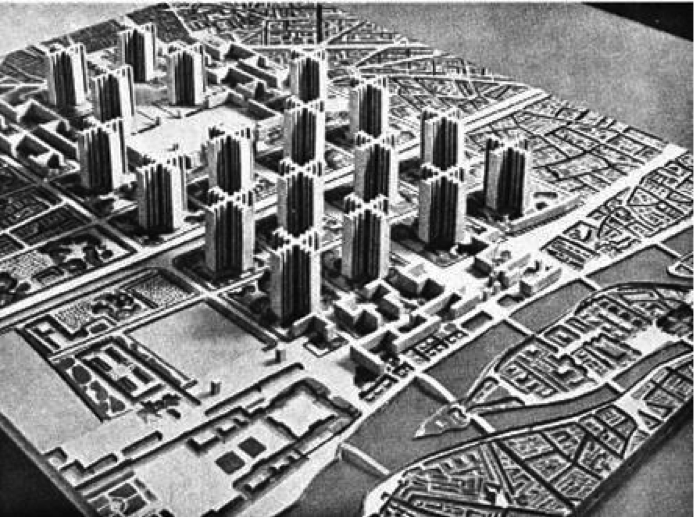

Jane Jacobs, author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, agreed that modernist urban planning should focus mainly on the human beings living in the community (“The Death and Life of Great American Cities”). She took a step further to the approach with the New Urbanism movement, which focused on building a sense of community and providing adequate resources for members of the neighborhood, defining what exactly needs to be done in order to cultivate useful urban spaces (“New Urbanism”). In her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, she cites her work in creating urban spaces that advocated for “four generators of diversity” to create effective economies. These are: mixed primary uses, short street blocks, buildings of various stages of age and repair, and density (“The Death and Life of Great American Cities”). She used three generators to curate neighborhoods that would serve the communities in the most advantageous way possible. According to Jacobs, effective neighborhoods need to “foster lively and interesting streets, make the fabric of the streets as continuous a network as possible, use parks, squares, and public buildings to intensify the fabric’s complexity, and foster a functional identity at the district level” (“The Death and Life of Great American Cities”). These pillars will allow neighborhoods to function overtime through community cooperation, fostering urban vibrancy and providing for long term advantages rather than short term.

Past works of public interest designers have inspired Bryan Bell to teach public interest design to those in the profession, so that it can be used consistently and successfully in projects throughout the future. The training will provide an in-depth study on methods of how design can fix critical issues faced by communities, using eight strategies outlined by Bell in a lecture at the NC State college of design. These strategies are: expanding roles and services, initiating projects, community engagement, advocacy, working in/for public policy arena, research, finding financial resources, education, integrating social agenda and design quality (“Bryan Bell (2.18.13).”). Bell says that’s it’s also very important to share these strategies with the communities, in order to remain transparent and allow for their feedback and concerns. Public interest design classes are beginning to takeoff at colleges as well, including here at NC State. During the class, students develop actual community requests from, starting with initial ideas that lead to clear design proposals. According to Design Corps, the study of modern day public interest design is a way of “enhancing an existing design practice and learning skills to become pro-actively engaged in community-based design through fee-based projects” (Design Corps). The practice is broad and applies to a variety of disciplines, representing a future trend of design that will adapt to the concept of client and changing economic conditions.

Designing for the needs of individuals is an extremely important aspect of design. In order for a design to be “good” it must be able to be used successfully by the person/people that it is designed for. In the past, William H. Whyte and Jane Jacobs have applied public interest design to the construction of urban spaces. Whyte focuses on the needs of the community members, and approaches his designs with a bottom-up approach that begins with an understanding of how people use the space, and how to make it more livable for them. Jacobs introduced the New Urbanist movement which focuses on four generators of diversity that build a sense of community within neighborhoods and serve communities in the most advantageous way possible. Architect Bryan Bell has modernized public interest design with his work for Design Corps, that fully immerses community members into the design process, particularly underserved communities that normally would not get the help they need. He has begun to spread the knowledge he has gained through public interest design by training young designers to carry out the practice and apply its methods when designing for communities. The practice of public interest design is an innovative practice that puts the main focus of design projects on the community’s needs, rather than the designer’s needs. Through the work of designers including Whyte, Jacobs, and Bell, public interest design has helped to curate effective spaces for communities that shape their environments and address their social, economic, and environmental challenges long into the future.

Works Cited

“Bryan Bell, AIA.” Architect. The Journal of the American Institute of Architects, 1 June 2011,

http://www.architectmagazine.com/aia-architect/aiavoices/bryan-bell-aia_o. Accessed 5 November 2016.

“Bryan Bell, Jr., AIA (1960-).” NC Modernist. Triangle Modernist Archive, Inc.,

http://www.ncmodernist.org/bbell.htm. Accessed 5 November 2016.

“Bryan Bell (2.18.13).” Vimeo, uploaded by NC State – College of Design, 2013,

Design Corps. Design Corps, 2016, https://designcorps.org. Accessed 5 November 2016.

“Public Interest Design.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 13 November 2016,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_interest_design. Accessed 5 November 2016.

“New Urbanism.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 13 November 2016.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Urbanism. Accessed 10 November 2016.

“The Death and Life of Great American Cities.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 2 June

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Death_and_Life_of_Great_American_Cities. Accessed 10 November 2016.

“William H. Whyte.” PPS. Project for Public Spaces, http://www.pps.org/reference/wwhyte/.

Accessed 10 November, 2016.