By Liz Chen

In July 2023, I learned I would be teaching a special topics course in the spring at NCSU, meaning I could construct a class on whatever I wanted, as long as it related in some way to graphic and experience design. As a recent NCSU graduate student interested in social justice, I carried an urgency to conduct impactful design research, examining educator systemic bias and its impact on underrepresented students in design education. In academia, where curriculum tends to be censored by Board of Trustee ideology and anti-DEI legislation threatens classroom sovereignty, it is increasingly vital to provoke change and advocate for equity and social justice. As a non-tenure track faculty member, I had a unique positionality as I did not feel pressure to please an institution through political neutrality. To me, this was an opportunity to develop a course aimed to strengthen the next generation of designers in their critical thinking skills. Specifically, “Design Ethics and Justice” encouraged students to challenge the status quo and embrace cultural humility.

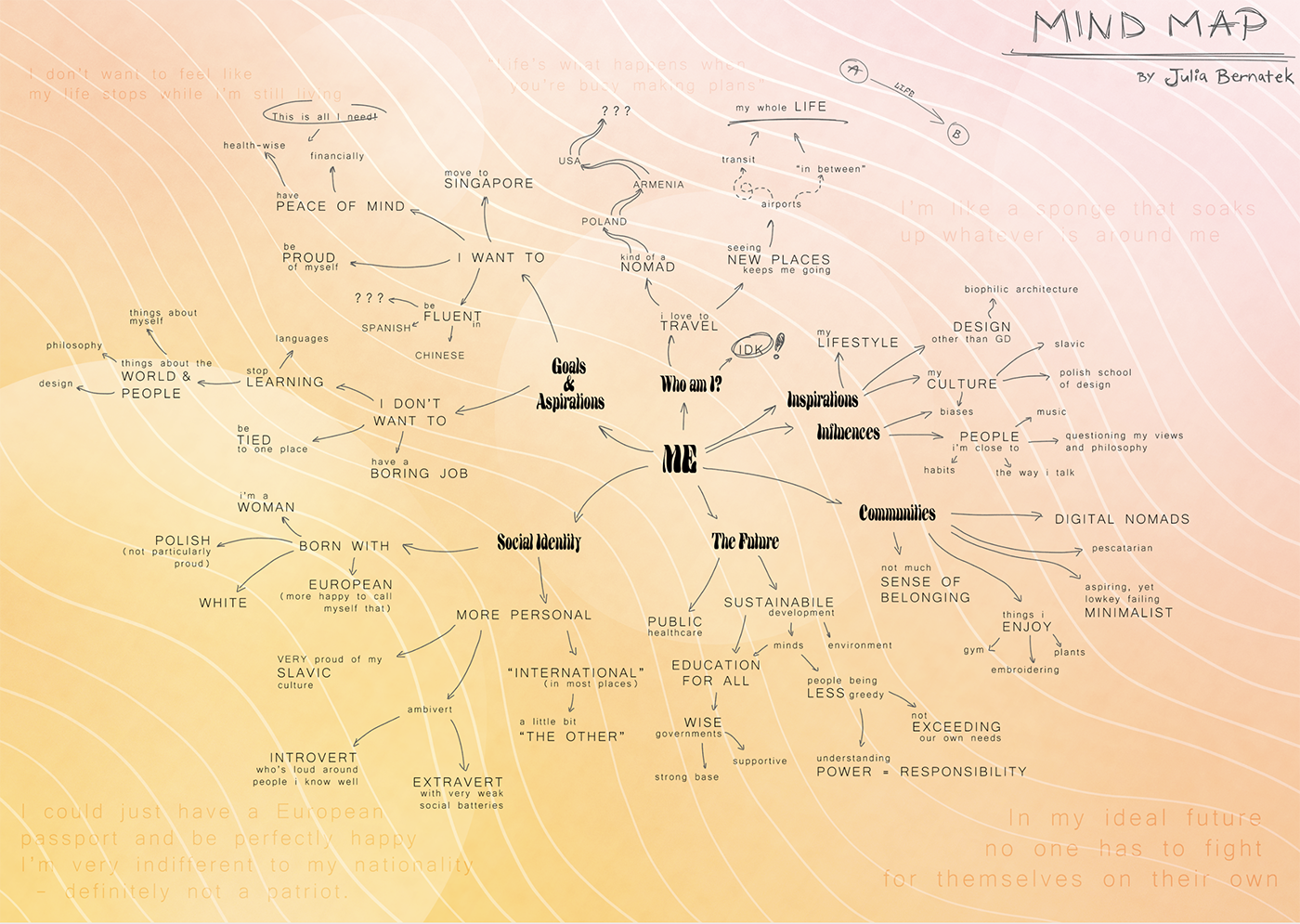

The course, which met weekly, began with a discussion on social identity and positionality. In the following weeks, we discussed intersectionality, ethics in design, design justice, disability justice, accessible design, decolonizing design, indigenous design, BIPOC design, design in a capitalist society, poetic research, data ethics, ludditism, and queer design. Projects included the creation of a visualization of student values, a zine that captured a conversation between a student and a person engaged in design with a historically marginalized background, and finally, students designed activities for their peers to participate in about topics covered in class.

Throughout the course, we relied on Miro for collaboration, community-building, and class activities. As an ode to the collage-esque aesthetic of our course Miro board, this visual essay aims to mimic Miro’s visual output whilst capturing the breadth of content – lectures, activities, visiting speakers, workshops, student work, and student reflections – that emerged from Design Ethics and Justice. At first glance, the visualization is messy, scattered, and full of breadcrumbs – this is largely on purpose, representative of how I initially conceptualized the course. Upon further inspection, there is structure within each section, labeled by topic and week, collaborators, and student projects. The flow of the course, though indicated by the week number, does not necessarily need to be followed chronologically (but can be traced by a thick yellow line). Student-written reflections are sprinkled throughout, captured via sticky notes, and placed in proximity to what the student is reflecting on. Some sticky notes are paired with visual reflections.

As an alum of this program, I was privy to the gaps in curriculum and the lack of diverse and intersectional instruction. Understanding that I could not speak adequately on issues in which I don’t have experience, I invited guest speakers with lived experience in the topics we explored. Through these visits, my perspective expanded: I was once again a student, and though the lines felt a bit blurred from the beginning, I realized that rejecting the binary and restricting roles of student vs. educator enhanced receptivity and flow of knowledge.

Although I attempted to design this course from the perspective of a learner who craved these conversations, I recognize that this course has tremendous room for improvement. If I were to facilitate this course in the future, I’d take a non-hierarchical pedagogical approach, opting for students to have more autonomy in the way the course is structured, the topics we cover, and project scopes. Practicing pedagogical co-design would imply that students are invested in the development of the course, providing insight into their interests, and shaping their educational experiences. In retrospect, I believe the course would benefit more community building, empowering students to bring their lived experiences into the classroom and creating an environment built on trust, conceptual exchange, and accountability.

Overall, I enjoyed many aspects of my year as an Assistant Teaching Professor at NC State. I’m grateful for the opportunity to mentor students and expose them to ideas and philosophies they may not have encountered during their academic careers.

Thank you to all collaborators in this course: Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD; Lexi Namer, Alexandra Grossi, Sadie Red Wing, Ashley Anderson, Shadrick Addy (and Victoria Gerson for the introduction), Randa Hadi, and Jarrett Fuller.

Most of all, thank you to my students who approached this course with openness, patience, and willingness to thoughtfully engage.

Liz Chen (she/they) is a graphic and user experience designer, writer, and educator based in Raleigh, NC. They received a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism (Reporting) with a minor in English from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2019 and a Master’s Degree in Graphic and Experience Design (MGXD) from North Carolina State University in 2023. Currently, Liz is an Assistant Professor of Graphic and Experience Design at NCSU and freelance graphic and UX designer. Their research interests include design ethics, design pedagogy, design justice and activism, and machine learning/AI.

Liz Chen (she/they) is a graphic and user experience designer, writer, and educator based in Raleigh, NC. They received a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism (Reporting) with a minor in English from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2019 and a Master’s Degree in Graphic and Experience Design (MGXD) from North Carolina State University in 2023. Currently, Liz is an Assistant Professor of Graphic and Experience Design at NCSU and freelance graphic and UX designer. Their research interests include design ethics, design pedagogy, design justice and activism, and machine learning/AI.

If you’re interested in design ethics and design justice and want to chat, email me at ebaileychen@gmail.com.

Isabel Bo-Linn is a multidisciplinary designer, researcher, and educator with experience in print, product, and UX/UI design. Their current research investigates the origins, influences, and possibilities of visual essays/narratives as pedagogical tools and design artifacts. Other active investigations include the potentials embodied interactive systems, experiments with type and image through emerging technologies, speculative design, as well as theories and methodologies of design pedagogy.

Isabel Bo-Linn is a multidisciplinary designer, researcher, and educator with experience in print, product, and UX/UI design. Their current research investigates the origins, influences, and possibilities of visual essays/narratives as pedagogical tools and design artifacts. Other active investigations include the potentials embodied interactive systems, experiments with type and image through emerging technologies, speculative design, as well as theories and methodologies of design pedagogy.

Jay Harlow is a Design + Product leader who specializes in simplifying complex systems, managing changes of scale and integration, and finding the overlap between the possible and the potential.

Jay Harlow is a Design + Product leader who specializes in simplifying complex systems, managing changes of scale and integration, and finding the overlap between the possible and the potential.

Rebecca Knowe works as a Senior User Experience Researcher at IBM, where she has focused on software design, concept research, and business strategy since 2013. She graduated from the NCSU Master of Graphic Design program in 2012, after several years of working as a freelance and in-house graphic designer.

Rebecca Knowe works as a Senior User Experience Researcher at IBM, where she has focused on software design, concept research, and business strategy since 2013. She graduated from the NCSU Master of Graphic Design program in 2012, after several years of working as a freelance and in-house graphic designer.

Saša Crkvenjaš is a graphic designer pursuing a Master’s degree in Graphic and Experience Design at North Carolina State University. Holding a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Graphic Design from the University of Florida, her passion lies in intercultural experiences, humanistic design, and innovative technologies. Her artistic journey began in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and expanded through experimental techniques and photography at United World College in Mostar. Saša’s work aims to connect people, places, and information, drawing inspiration from her experiences in two diverse cultures. She specializes in UI/UX design and has a keen interest in leveraging AI and ML technologies to create practical and visually pleasing solutions that promote well-being, accessible education, and cross-cultural understanding.

Saša Crkvenjaš is a graphic designer pursuing a Master’s degree in Graphic and Experience Design at North Carolina State University. Holding a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Graphic Design from the University of Florida, her passion lies in intercultural experiences, humanistic design, and innovative technologies. Her artistic journey began in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and expanded through experimental techniques and photography at United World College in Mostar. Saša’s work aims to connect people, places, and information, drawing inspiration from her experiences in two diverse cultures. She specializes in UI/UX design and has a keen interest in leveraging AI and ML technologies to create practical and visually pleasing solutions that promote well-being, accessible education, and cross-cultural understanding.

Randa Hadi (MGD ‘20)

Randa Hadi (MGD ‘20)

Rachael Paine is an Assistant Professor of Graphic Design and Human-Centered Design at Virginia Tech. She has a Bachelor’s and Master’s in Graphic Design and a Ph.D. in Design from North Carolina State University. Rachael has worked as an adjunct instructor at NC State and as a full-time user experience designer for a multinational analytics software developer. Various design research publications have featured Rachael’s work, and she has presented and participated at conferences both nationally and abroad including the International Conference on Design Principles & Practices, Surface AIGA Design Conference, MODE ReConnect Motion Design Education Summit, and Architecture_MPS Education, Design, and Practice. Rachael’s most recent work was her study conducted for her Ph.D. dissertation at North Carolina State University. Her study addressed how rare disease caretakers search online for health information and how interfaces can respond to a user’s cognitive state. Her research interests include user experience design, health communications, responsive user interfaces, and interactive information design.

Rachael Paine is an Assistant Professor of Graphic Design and Human-Centered Design at Virginia Tech. She has a Bachelor’s and Master’s in Graphic Design and a Ph.D. in Design from North Carolina State University. Rachael has worked as an adjunct instructor at NC State and as a full-time user experience designer for a multinational analytics software developer. Various design research publications have featured Rachael’s work, and she has presented and participated at conferences both nationally and abroad including the International Conference on Design Principles & Practices, Surface AIGA Design Conference, MODE ReConnect Motion Design Education Summit, and Architecture_MPS Education, Design, and Practice. Rachael’s most recent work was her study conducted for her Ph.D. dissertation at North Carolina State University. Her study addressed how rare disease caretakers search online for health information and how interfaces can respond to a user’s cognitive state. Her research interests include user experience design, health communications, responsive user interfaces, and interactive information design.

Victoria Gerson, MGD ‘20, is a designer, researcher, and educator from Miami, FL. She has Brasilian heritage and comes from a line of teachers who inspired her to become an educator.

Victoria Gerson, MGD ‘20, is a designer, researcher, and educator from Miami, FL. She has Brasilian heritage and comes from a line of teachers who inspired her to become an educator.

Michael Carbaugh is currently a Senior UI/UX Designer at Campminder, a SaaS company that builds summer camp management software. In his professional practice Michael enjoys being a generalist, striving to find the ideal balance between seeing design through a strategic lens and jumping into the details of day-to-day design work. Before working at Campminder he spent a decade as a User Experience Designer for large enterprise companies including IQVIA and IBM, occasionally taking on freelance side projects for traditional graphic design work.

Michael Carbaugh is currently a Senior UI/UX Designer at Campminder, a SaaS company that builds summer camp management software. In his professional practice Michael enjoys being a generalist, striving to find the ideal balance between seeing design through a strategic lens and jumping into the details of day-to-day design work. Before working at Campminder he spent a decade as a User Experience Designer for large enterprise companies including IQVIA and IBM, occasionally taking on freelance side projects for traditional graphic design work.

Kelly Murdoch-Kitt

Kelly Murdoch-Kitt  Dr. Denielle Emans

Dr. Denielle Emans